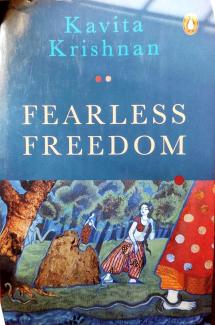

(We share two excerpts from Liberation editor Kavita Krishnan’s new book Fearless Freedom, published this month by Penguin Random House India)

An Alternate Politics of Parenting

WHRTHER it is ‘Bharat Mata’ or ‘Gau Mata’ (Mother Cow), it seems as though ‘mothering’, in Indian politics today, is a pretext for violence and hate. In particular, parenting a daughter, in our dominant political discourse, amounts to “protecting” her from exercising her own autonomy, in particular, from loving someone from a prohibited community or gender. And parenting a son, in the same discourse, amounts to training him to hate the people of other communities or countries. Are there other ways in which the love and pain of parenthood figure in Indian politics?

In 1997, when student leader Chandrashekhar (who was a close friend and comrade of mine) was killed at the behest of the criminal don and RJD MP Shahabuddin, his mother Kaushalya Devi had led a sustained movement demanding justice. Since 2016, Radhika Vemula has led a struggle to demand justice for her son - Ambedkarite student activist Rohith, who took his own life following persecution by the authorities at Hyderabad University, under pressure from Central Government Ministers and Sangh leaders. The Prime Minister, in a vain attempt to quiet the rage that followed Rohith’s death, said that Rohith was “Maa Bharti Ka Laal” (a beloved son of Mother India) - even as the BJP kept slandering Maa Radhika and her son! Fathima Nafees, the mother of JNU student Najeeb (who vanished from the JNU campus following a thrashing by a group of ABVP cadres) is also leading an agitation to find her son.

Chanderpati of Haryana has been fighting for justice for her son Manoj who was killed along with his wife Babli in Haryana (by Babli’s family members) for marrying within the same gotra. The abduction and ‘honour’ killing of her son Nitish Katara in 2002 turned Neelam Katara into a tireless campaigner against caste-patriarchal crimes against love.

These mothers offer us a politics which restores the humanity and the pain to motherhood. In contrast to the rhetoric about ‘Maa Bharti’, these women, with the unbearable pain at the loss of their child, restore to the image of the mother, the love, labour and loss of mothering.

Satya Rani and Shahjahan: Mothers Who Became Sisters in Struggle

In 1979, Satya Rani Chadha’s daughter Shashi Bala, married for less than a year, was one of the thousands of young brides who died of ‘kitchen stoves bursting’ after their parents failed to meet the ever-increasing demands from the husband and in-laws for dowry. Satya Rani knew her daughter had not committed suicide - because Shashi Bala’s husband had been threatening to kill his wife if she failed to meet their demands for dowry. In the same year, a woman worker, Shahjahan Apa also lost her daughter Noorjahan to a dowry killing.

In the massive anti-dowry protests that hit the streets of Delhi in the 1980s, Satya Rani and Shahjahan met - and three years after the deaths of their daughters, they together set up the feminist organisation Shakti Shalini to help women facing domestic violence. As Shahjahan Apa put it, they “resolved to use the death of (their) daughter as the impetus to fight for the rights of others.”

Shahjahan Apa later said, “In our society, the men get a free servant when they marry, but I believe that men and women are partners in marriage and stand on equal footing. Today our own government betrays us. The police betray us. … But each day I board the bus that will bring me to our office so that I can meet with the women who have nowhere else to turn. There is a saying in Hindi: ‘Meri shakti, meri beti,’ which means, ‘My strength is my daughter.’”

Our mainstream political discourse full of shrill slogans about ‘saving’ daughters and worshipping mothers. Yet, in a country where daughters are considered undesirable and dispensable, how come we hear so little about these two mothers who turned the love for and loss of their daughters into strength offered to other women in need?

A Father’s Search For His Son

On March 1 1976, during the Emergency, a young student at the REC Calicut (today known as NIT Calicut) in Kerala named Rajan was picked up by the police and taken to a detention camp. He then ‘disappeared.’ His father, a retired Hindi teacher Professor TV Eachara Varier, began a futile hunt for his son. Ministers, Chief Ministers, all knew the truth but none would admit it to him. His stubborn struggle eventually unearthed the truth: Rajan had died in police custody following brutal torture.

Rajan had been arrested as a “Naxalite” – with no evidence linking him to any crime. His story became synonymous with the Emergency and its attack on civil liberties and human rights. He had been subjected to a particularly brutal form of torture known as uruttal (rolling) in which a heavy wooden log would be rolled over their thighs; and then kicked in the stomach by a police officer with heavy boots.

Professor Eachara Varier wrote a book about his experience of searching for his son. He described the way in which Rajan’s mother (who became insane) never stopped expecting her son to return. He ended the book with an account of a visit to the Kakkayam detention camp where his son was tortured and killed. His final words leave the reader with a question and a challenge: “I still have no answer to the question of whether or not I feel vengeance. But I leave a question to the world: why are you making my innocent child stand in the rain even after his death?

I don’t close the door. Let the rain lash inside and drench me. Let at least my invisible son know that his father never shut the door.”

Rajan’s father wrote, “I should not leave the new generation to that wooden bench and the rolling.” Those words should shame and haunt us today because brutal torture - including the ‘uruttal’ torture – continues in our police stations. These forms of torture were not an “excess” of the Emergency – they are part of casual, everyday, routine policing in India. For the poor, for the Dalits, adivasis and minorities, every day is an ‘Emergency’, irrespective of who is in power.

In 2018, again in Kerala, 67-year-old single-mother Prabhavathi Amma succeeded in winning a conviction of the policemen who performed the same brutal rolling torture on her son Udayakumar, a scrap collector 13 years ago. Udayakumar had been picked up by the police on charges of petty theft - and killed under custodial torture. Prabhavati said their family was so poor that they never had the money to get a photograph taken of Udayakumar: the only picture she has of her son is of his dead body. When a Special CBI Court convicted the police officers for her son’s custodial killing, Prabhavati said exactly what Eachara Varier had said decades ago: “I should do this for my son, so that no other mother will have to go through what I went through.”

These fathers and mothers lost everything when their sons were taken, tortured and killed – they struggled so that others should be spared the same fate. Our callous tolerance of custodial torture, as a society, lets down these parents. It is even more obscene that such custodial torture is rationalised as “national security” and “protecting the Motherland,” and the voices arguing in favour of the principles of human rights and civil liberties are vilified as “anti-national.”

Towards Fearless Freedom

“You write in order to change the world, knowing perfectly well that you probably can't, but also knowing that literature is indispensable to the world ... The world changes according to the way people see it, and if you alter, even but a millimeter the way people look at reality, then you can change it.” – James Baldwin Kal ka geet liye honthon par, aaj ladaai jaari hai (With tomorrow’s song on our lips, we fight today’s battles) – Maheshwar

In December 2012 and January 2013, the anti-rape movement that swept Delhi heard bold cries demanding ‘Fearless Freedom’ – and also demanding ‘naari mukti, sabki mukti’ (freedom for women, freedom for all).

Women (and indeed all of us – women, LGBTQIA persons, men) can be fully free only when humanity is free – and that, as I see it, will need us to throw off the yoke of the entire oppressive, exploitative structure. It will, in other words, need a revolution, a complete change of the the way human beings stand in relation to each other and to nature.

What’s the point of imagining a revolutionised world free of all hierarchies, it isn’t going to be a reality in our lifetime, I am often asked.

Revolutionary goals are like a compass on a long march – it may take very long to reach the destination, and the destination may not be in sight, but a compass makes sure we march in the right direction and do not lose our way.

If you’re putting together a thousand-piece jigsaw puzzle, you can do it only with the full picture clear in your head. Without the full picture, you can’t connect the little pieces to each other.

We need to keep tomorrow’s song on our lips in today’s battles – and that’s what gives meaning and direction to today’s battles. We need to hope and work for the day that all women and all of humanity shall be free, and all hierarchies shall be history – and it’s then that we are able to see today’s struggles whole, rather than piecemeal and disconnected from each other.

Revolutionary goals aren’t empty dreams made up of nice ideas. Revolutionary dreams are anchored firmly in the earth – and humans working together can make those dreams come to life on this earth. With that revolutionary destination firmly in our sights, we are able to recognise how each of the less distant goals we seek for ourselves, cannot be achieved without a struggle for women’s autonomy at their core.

‘Autonomy’ isn’t about mere ‘choice’ made by an individual – it isn’t like choosing between various brands at a supermarket. ‘Autonomy’ in a feminist sense is necessarily autonomy – to whatever extent possible – from social and economic structures, and it is never autonomy for oneself, to hurt the rights and liberties of other women, other oppressed people.

I have in mind Prachi Trivedi, one of the protagonists of the 2012 documentary film by Nisha Pahuja, ‘The World Before Her’. Prachi is a young woman, a trainer at a Durga Vahini camp, in which young girls from rural India are taught to wield weapons and hate Muslims. Prachi’s father, a VHP leader, once burnt her foot, to punish her for lying – but Prachi says it’s okay for him to do that, since he allowed her to live, rather than be killed at birth like so many other baby girls in India. Prachi is not conventionally feminine, and she is not interested in getting married: but she accepts that her father will take that decision for her. The thrill that women in the Durga Vahini camp get from wielding weapons, raising slogans, and learning martial arts moves is all circumscribed by an ideology that tells them women must be subservient to men; that women’s purpose is to give birth; and that women are required to be step out of domestic roles and be battle-ready only to ‘save’ the country from Muslims – i.e to inflict violence on minorities. This is not feminist autonomy. A young woman who joins the Durga Vahini experiences, briefly, what may feel like a taste of liberty – but she’s “allowed” that autonomy by a patriarchal father and a fascist organisation only in so much as she can hate and inflict violence on Muslim minorities.

The same film also follows young women who are participants in a Miss India beauty pageant. Does the world of the beauty pageant offer autonomy? The young women’s bodies are subjected to Botox and to humiliating tests (such as when all their faces are covered to allow judges to judge the beauty of their legs alone). The pageant encourages every woman to compete fiercely with other women – each is out for her own. And yet the pageant not only disallows mutual solidarity, it also erases individuality: so much so that a contestant’s own mother is unable to recognise her daughter in the line-up of contestants who all look the same!

Both the Durga Vahini camp and the beauty pageant boot camp offer young women what can pass for ‘empowerment.’ But both demand a measure of self-hate: the Vahini wants women to internalise and become agents of a brutal patriarchy, while the Miss India pageant wants women to internalise the notion that “beauty” requires their bodies to be subjected to all sorts of “corrections”, indignities and humiliations. In addition, of course, the Vahini camp requires young girls and women to learn to hate Muslim men and women, and trains them to attack the autonomy of other Hindu women who may love or marry a Muslim!

To wrest autonomy from oppressive and exploitative structures calls for collective struggles, for drawing strength from each other, not in competition with each other. That’s why a feminist quest for autonomy can’t be about a few individual women “breaking the glass ceiling” in competition with a handful of other men and women. A recently published Feminism for the 99%: A Manifesto asserts, “we have no interest in breaking the glass ceiling, while leaving the majority of women to clean up the shards.”

In Indian traditions of art, we have the wonderful image of the ‘Abhisarika’ – the woman who braves all sorts of dangers to venture out into the stormy night, through forests full of snakes, to meet her lover. Comparing the women who came out with candles and torches to march against rape in Delhi in December 2012 to the Abhisarika, Shuddhabrata Sengupta wrote that the Abhisarika was always seen as a source of light: “Her desire is a flame that lights up everything around her. In the folk songs of Punjab, she can be a firefly, a restless, wandering jugni. And women, together, out on the streets, out to claim each hour, each watch of the night, can light up an entire forest of a city with their flickering, blazing fire.”

We need women to be Abhisarikas today: with their desires – for lovers, yes, but also for the simple pleasure of a walk on the street or a cup of a chai at a street corner, for reading and research, for adventure, for andolans, for revolution – to light up everything around them. And when many women become Abhisarikas, the streets and the dark nights will be much safer. Imagine a woman alone on the street at night – and we imagine danger; but imagine a street full of women going about their own business and pleasure, and to women, such a street immediately seems safe!

These Abhisarikas can change the ways in which we imagine and shape our relationships, our society, our families, our movements. Instead of worrying about proving they are a “good” (obedient) rather than “bad” (disobedient) daughter, sister, or partner/spouse, they can instead find ways of feeling comfortable and confident in their autonomous skin without feeling the need to seek “permission” and validation for that autonomy. Older women can be Abhisarikas too – they can respect their own autonomy, and also that of younger women and girls in their own households.

If you’re a mother or a parent, you may ask, “It’s all very well to speak of “fearless freedom”, but of course my daughter is going to feel fear in a world where sexual violence is so rampant. Well, yes – but you do have it in your power as a parent to free your daughter of the fear that speaking up about sexual harassment or violence will mean having her parents curtail her education. That in itself would be a huge step towards giving your daughter the gift of fearless freedom. Likewise you could free your child (of any gender) of the fear that coming out to their parents as lesbian or gay or trans could lose them the love and acceptance of their parents.

We can, in fact must, put women’s autonomy at the centre of our struggles against fascism, against capitalism, against Brahmanism, against patriarchy and against heteronormativity. We can unlearn the habit deeply ingrained even in women of dividing ourselves up into “good” and “bad” women. At home, at work, in our communities and neighbourhoods, we can find ways to enable ourselves and other women to organise, to campaign, to find support and solidarity, and to fight.

Will this book change the world? Perhaps not. But if it can even alter by a millimetre how you and we look at women’s autonomy and autonomous women – if we can begin to admire and cherish women’s bekhauf azaadi, their veera sutantiram, their fearless freedom – perhaps we can change the world!

Liberation Archive

- 2001-2010

-

2011-2020

- 2011

- 2012

- 2013

- 2014

- 2015

- 2016

- 2017

- 2018

- 2019

-

2020

- Liberation, JANUARY 2020

- Liberation, FEBRUARY 2020

-

Liberation, MARCH 2020

- Delhi 2020 Verdict – A Much Needed Blow to the Modi-Shah Regime

- Modi and Trump: Two Tyrants Meet in an Extravaganza Wasting Crores! But Does It Benefit India and Indians?

- SC Verdict on Reservation in Promotions

- Population Control Is Anti Women, It Is Not Reproductive Justice

- The Countrywide Upsurge against CAA-NRC-NPR: What We Have Achieved and What Comes Next

- Kanpur's women-led NRC protest has overturned local power structures: ‘They aren't listening to us’

- Campaign Diary: Comrade Kavita Krishnan in Bihar

- Against Fascism – Women Shall Fight And Win! 8th National Conference of AIPWA Held at Udaipur

- Rise In Rage Against Sexual Assault By A Mob Against Students At Gargi College And By Delhi Police Against Jamia Millia Islamia Students

- CPIML condemns slapping of NSA on Dr Kafeel

- Release Chauri Chaura Padyatris without Delay

- Sanitation Workers’ Struggle in Bihar Against Outsourcing

- Preparations on for Vidhan Sabha March on 25 February

- Left Parties Report on Police Brutality in Bilriyaganj (Azamgarh)

- False Cases slapped on Party Leaders in Pilibhit

- Fearless Freedom

- Liberation, APRIL 2020

- Liberation, MAY-JUNE 2020

- Liberation, JULY 2020

- Liberation, AUGUST 2020

- Liberation, SEPTEMBER 2020

- Liberation, OCTOBER 2020

- Liberation, NOVEMBER 2020

- Liberation, DECEMBER 2020

- 2021-2030

Charu Bhawan, U-90, Shakarpur, Delhi 110092

Phone: +91-11-42785864 | Fax:+91-11-42785864 | +91 9717274961

E-mail: info@cpiml.org