SOME sections are stirring the communal pot in Assam on the eve of the publication of the final NRC list by filing an FIR against protest poetry by Bengali-speaking Muslims. Reclaiming and embracing the abusive term used colloquially to describe them - “Miyah”, this poetry defies communal and linguistic bigotry, and expressed pride in “Miyah” identity. “Miyah” is a term that in Urdu connotes “gentleman”, but has become an abusive term to describe Bengali-origin Muslims in Assam.

In his poem, ‘Shiter shishir bheja raat’ (On a damp wintry night), Bhupen Hazarika had hoped for his poetry to be “the blood-red warmth of smouldering cinders in the crumbling hut of an unclad peasant/the tremendous might of burning hunger in an empty-stomached farmer/a sweet sense of security for some terrified minority community.” Today, with the sword of the NRC final list and the Citizenship Amendment Act hanging over them, the Bengali-speaking Muslims of Assam are perhaps the most terrified. Surely this is a time to stand strong by the poets voicing the concerns of that community - its fear, but also its assertion of its dignity, humanity, and voice?

The demand from some progressive quarters that these poets write exclusively in Assamese rather than in the minority language is also disturbing. Many of the Miyah poets do, in fact, write extensively Assamese. Why should they not also write in a language which is today being stigmatised? Mainstream Bollywood cinema often divides Muslims into “good Muslims” and “bad Muslims.” There seems to be an attempt now to say that “good Miyahs” are the ones who do not write in any language but Assamese, while the Miyah poets - thanks both to their language and their subject matter - are “bad Miyahs.”

We reproduce a statement issued in support of the Miyah poets of Assam, as well as some poems by those poets.

Public Statement In Support of Miyah Poets

(This statement was issued by over 200 signatories)

On 10 July 2019, an FIR was filed against ten Miyah poets and other activists from Assam under five different sections of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) and the Telecommunications Act for a poem titled ‘Write it Down, I am a Miyah’ written by senior Miyah poet, Hafiz Ahmed. The FIR accused the poets and activists, amongst other things, of depicting the Assamese people as “xenophobic in the eyes of the whole world” and posing a “serious threat to the Assamese people as well as towards the national security and harmonious social atmosphere.”

A week later, at least three more FIRs were filed over the same poem. Meanwhile, several of these poets/activists are being subjected to a barrage of online trolling and intimidation by certain individuals on social media and WhatsApp. These include death threats, rape threats and other explicit forms of harassment. There is also a wider attempt to malign the young Miyah poets and in fact, the entire Miyah community, through derogatory, lurid and baseless stereotypes. This malicious campaign only adds fuel to the existing sentiment of hostility against Bengali-origin Muslims of Assam who remain highly vulnerable to ethno-nationalist majoritarianism and anti-immigrant rhetoric in the state.

We unequivocally condemn such attempts to malign and criminalise the Miyah poets. Poetry can be a spontaneous and legitimate medium of expression of collective trauma, grievances and emotions. In the absence of other avenues, it often becomes the sole medium of speaking truth to power. Every single individual and community has, and should have, the natural right to do so without the fear of perverse consequences, including punitive action (such as FIRs). The criminalisation of any poetry marks the death of a healthy, democratic and humane society that we want Assam to be. In this context, we see Miyah Poetry as a legitimate form of literary protest against the victimisation of Bengal-origin Muslims of Assam.

In this regard, we remind the principal stakeholders - the judicial system, on which we rest many of our hopes, and the media - of the fundamental rights guaranteed through the highest laws of the country i.e. those enshrined in the Constitution: Article 14 ensuring equality before the law, Article 15 defining equality of opportunity, and Article 19 upholding freedom of speech and expression, subject to “reasonable restrictions”. We, thus, expect and urge the government and other mandate holders to uphold the constitutional rights of all citizens, which also include the right of writers to speak and write freely without fear of fear, harm or intimidation. We believe that anyone attempting to impinge on these fundamental rights with arbitrariness and frivolous interpretations must face the full force of the law.

Further, we strongly condemn the manner in which certain lines from some old poems have been selectively quoted, distorted and taken out of context to project them as “anti-Assamese” or “anti-social”, as also highlighted in the recent statement released by the Miyah poets/activists. These are labels that only sharpen Assam’s brittle faultlines and create conditions for ethnic and communal violence. We urge all parties to refrain from using such simplistic and baseless titles against the poets.

Finally, we unequivocally condemn the cyber bullying, harassment and threats that the Miyah poets, activists and their friends are being subjected to. Such conduct is not just downright unacceptable in a civil society, but also fall under the ambit of criminal offences. We urge all members of Assam’s civil society, including prominent intellectuals, to publicly condemn the trolling of Miyah poets/activists and urge the police to take necessary action against the perpetrators.

The final draft of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) is about to be published on 31 July. In this context, the timing of the controversy and the vilification of the poets point to dangerous times ahead. We appeal to all people to assert their voices against hate, suspicion, chauvinism and censorship of literary expressions.

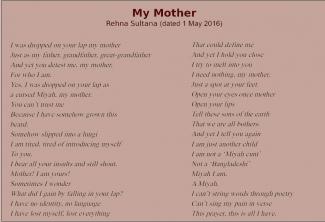

My Mother

Rehna Sultana (dated 1 May 2016)

I was dropped on your lap my mother

Just as my father, grandfather, great-grandfather

And yet you detest me, my mother,

For who I am.

Yes, I was dropped on your lap as

a cursed Miyah, my mother.

You can’t trust me

Because I have somehow grown this

beard.

Somehow slipped into a lungi

I am tired, tired of introducing myself

To you.

I bear all your insults and still shout,

Mother! I am yours!

Sometimes I wonder

What did I gain by falling in your lap?

I have no identity, no language

I have lost myself, lost everything

That could define me

And yet I hold you close

I try to melt into you

I need nothing, my mother.

Just a spot at your feet.

Open your eyes once mother

Open your lips

Tell these sons of the earth

That we are all bothers.

And yet I tell you again

I am just another child

I am not a ‘Miyah cunt’

Not a ‘Bangladeshi’

Miyah I am,

A Miyah.

I can’t string words through poetry

Can’t sing my pain in verse

This prayer, this is all I have.

I beg to state that

Khabir Ahmad

(This poem, written in the wake of the Nellie Massacre of 1983, can be considered a forerunner of Miyah poetry. This poem raises a crucial question: should a majority get to name and define a minority community, even if the name is not a derogatory ‘Miyah’, but is instead, say, ‘neo-Asomiya’ which is the term Jyotiprasad Agarwala used to embrace the Bengali-origin Assamese?)

I beg to state that

I am a settler, a hated Miyah

Whatever be the case, my name is

Ismail Sheikh, Ramzan Ali or Majid Miyah

Subject - I am an Assamese Asomiya

I have many things to say

Stories older than Assam’s folktales

Stories older than the blood

Flowing through your veins

After forty years of independence

I have no space in the words of beloved writers

The brush of your scriptwriters doesn’t dip in my picture

My name left unpronounced in assemblies and parliaments

On no martyr’s memorial, on no news report is my name printed

Even in tiny letters.

Besides, you haven’t yet decided what to call me -

Am I Miyah, Asomiya or Neo-Asomiya?

And yet you talk of the river

The river is Assam’s mother, you say

You talk of trees

Assam is the land of blue hills, you say

My spine is tough, steadfast as the trees

The shade of the trees my address…

You talk of farmers, workers

Assam is the land of rice and labour, you say

I bow before paddy, I bow before sweat

For I am a farmer’s boy…

I beg to state that I am a

Settler, a dirty Miyah

Whatever be the case, my name

Is Khabir Ahmed or Mijanur Miyah

Subject - I am an Assamese Asomiya.

Sometime in the last century, I lost

My address in the storms of the Padma

A merchant’s boat found me drifting and dropped me here

Since then I have held close to my heart this land, this earth

And began a new journey of discovery

From Sadiya to Dhubri…

Since that day

I have flattened the red hills

Chopped forests into cities, rolled-earth into bricks

From bricks built monuments

Laid stones on the earth, burnt my body black with peat

Swam rivers, stood on the bank

And dammed floods

Irrigated crops with my blood and sweat

And with the plough of my fathers, etched on the earth

A…S…S…A…M

Even I waited for freedom

Built a nest in the river reeds

Sang songs in Bhatiyali

When the Father came visiting,

I listened to the music of the Luit

In the evening stood by the Kolong, the Kopili

And saw on their banks gold.

Suddenly a rough hand brushed my face

On a burning night in ‘83

My nation stood on the black hearths of Nellie and screamed

The clouds caught fire at Mukalmua and Rupohi, Juria,

Saya Daka, Pakhi Daka - homes of the Miyahs

Burnt like cemeteries

The floods of ’84 carried my golden harvest

In ’85 a gang of gamblers auctioned me

On the floor of the Assembly.

Whatever be the case, my name

Is Ismail Sheikh, Ramzan Ali or Mazid Miyah

Subject - I am an Assamese Asomiya.

Write Down 'I am a Miyah'

(This poem by Hafiz Ahmed seems inspired by ‘Identity Card’, the 1964 poem by Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish. Translated by Shalim M. Hussain)

Write Write Down I am a Miya

My serial number in the NRC is 200543

I have two children

Another is coming

Next summer.

Will you hate him

As you hate me?

Write I am a Miya

I turn waste, marshy lands

To green paddy fields

To feed you.

I carry bricks

To build your buildings

Drive your car

For your comfort

Clean your drain

To keep you healthy.

I have always been

In your service

And yet you are dissatisfied!

Write down I am a Miya,

A citizen of a democratic, secular, Republic

Without any rights

My mother a D voter,

Though her parents are Indian.

If you wish kill me, drive me from my village,

Snatch my green fields

Hire bulldozers to roll over me.

Your bullets

Can shatter my breast for no crime.

Write I am a Miya

Of the Brahamaputra

Your torture

Has burnt my body black

Reddened my eyes with fire.

Beware! I have nothing but anger in stock.

Keep away!

Or

Turn to Ashes.

Liberation Archive

- 2001-2010

-

2011-2020

- 2011

- 2012

- 2013

- 2014

- 2015

- 2016

- 2017

- 2018

-

2019

- JANUARY-2019

- FEBRUARY-2019

- MARCH-2019

- APRIL-2019

- May-2019

- LIBERATION, JUNE 2019

- Liberation JULY 2019

-

LIBERATION, August 2019

- August 15, 2019: Reclaim the Spirit of the Freedom Movement to Foil the Fascist Design of the Modi Government

- Stop Mob Lynching! Guarantee Justice for Tabrez!

- Modinomics 2.0 and Bahi-Khata 2019

- Protest against Railway Privatisation and Corporatisation

- Sovereign Foreign Debt: Is the Government Paving the Way for India's Bankruptcy?

- 'If People are Lynched for Not Saying Jai Shree Ram, I Will Certainly Protest'

- Delhi Factory Fires

- Sewer Deaths And The Robot Lie

- Wolf in Granny's Clothing: Exclusion Masquerades as Education

- Quality in School Education Cannot be Addressed Through Volunteerism

- Flood Havoc in Assam and Bihar

- Modi Regime Fans Islamophobia, Cracks Down On Rights

- In Solidarity With Miyah Poets

- Fresh Attacks On Universities -- DU Syllabus: Might Is Right

- An Open Letter From the Walls of JNU

- German Envoy Touches Feet Of Golwalkar's Statue At RSS HQ

- Draconian And Anti-Democratic Amendments To Laws

- Second Monthly London Vigil Against Fascism And Hindu Supremacy in India

- Sonbhadra: Adivasis Massacred With Police and Government Complicity

- Santosh Rana (1942-2019): Tireless Fighter For Dignity and Democracy for the Oppressed

- Red Salute To Comrade AK Roy

- Every Second ST, Every Third Dalit And Muslim In India Is Multi-Dimensionally Poor - Global MPI Index

- CPIML Appeal: Contribute to Flood Relief in Bihar and Assam

- Liberation, SEPTEMBER 2019

- Liberation, OCTOBER 2019

- Liberation, NOVEMBER 2019

- Liberation, DECEMBER 2019

- 2020

- 2021-2030

Charu Bhawan, U-90, Shakarpur, Delhi 110092

Phone: +91-11-42785864 | Fax:+91-11-42785864 | +91 9717274961

E-mail: info@cpiml.org